Background: Recent evidence highlights the critical influence nurses may have in antimicrobial stewardship (AMS). However, nurses’ express knowledge gaps and a lack of confidence in leading AMS interventions.

Sahar Momin, RN, MPH1*, Deanne J. O’Rourke, RN, PhD, GNC(C)1, Misty Fortier, RN, MN1, and Valerie Grdisa, RN, PhD1

1 Canadian Nurses Association, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada

*Corresponding Authors

Sahar Momin

Canadian Nurses Association

Ottawa, Ontario, Canada

Email: shr.momin@gmail.com

Article history:

Received 2 May 2025

Received in revised form 18 June 2025

Accepted 24 July 2025

ABSTRACT

Background: Recent evidence highlights the critical influence nurses may have in antimicrobial stewardship (AMS). However, nurses’ express knowledge gaps and a lack of confidence in leading AMS interventions.

The AMS competencies framework was developed to address these challenges by providing a foundation for optimizing AMS-related nursing interventions with guidance and expected competencies that can be adapted to different practice settings and nursing categories.

Methods: The framework development began with a literature review of nurses’ role in AMS across all nursing practice settings and was followed by a cross-Canada survey that involved 261 nurses, with 94% of respondents in non-prescribing roles and 6% in prescribing roles (nurse prescribers). Key survey findings were explored in virtual focus groups. Findings from the literature review, survey, and focus groups informed the initial draft of the AMS competency framework. The draft underwent internal review, and external validation through a Delphi Method with 33 reviewers and achieved high agreement (over 90%) on competency statements.

Results: The AMS competency framework is organized within a matrix of seven AMS domains, nurses’ roles, and the competencies (knowledge, skills, attitudes) that nurses and nurse prescribers require to participate in AMS within their practice setting. The competencies are broadly divided into three types: Core, additional, and optional competencies. Additionally, an evaluation framework provides individual nurses and partners with potential guidance and approaches to measure outcomes associated with the achievement of the AMS competencies.

Conclusion: Nurses’ impact on antimicrobial resistance (AMR) and involvement in AMS activities can have far-reaching benefits because nurses are at the forefront and interface across numerous care and practice settings. However, nurses’ engagement in AMS varies greatly and can be impacted by both individual factors (e.g., knowledge level, confidence, engagement) and contextual influences (e.g., workload, resources, leadership support, and advocacy to support nurses’ role in AMS). Coupled with contextual supports, the AMS competency framework represents an evidence-informed approach to define and support the knowledge, skills, and attitudes needed to maximize nurses’ role in AMS.

KEYWORDS

antimicrobial stewardship, antimicrobial resistance, nurses, competencies, evaluation

INTRODUCTION

Antimicrobial resistant infections are infections caused by organisms resistant to existing lines of antimicrobials. These types of infections are becoming more common and increasingly difficult to treat. As a result, antimicrobial resistance (AMR) is a significant and growing threat to human, animal, and environmental health in Canada and across the globe (PHAC, 2023; World Health Organization, 2018).

Antimicrobial stewardship (AMS) is a system-wide approach that recognizes the role of individuals seeking care/services, professionals, prescribers, and the public in appropriate antimicrobial use. It includes coordinated interventions designed to promote, improve, monitor, and evaluate appropriate antimicrobial use to preserve antimicrobial effectiveness while promoting and protecting health (PHAC, 2023).

To increase the understanding and application of AMS approaches among health professionals and prescribers, the Pan-Canadian Framework for Action on Antimicrobial Resistance and Antimicrobial Use emphasizes that the principles pertaining to AMR and appropriate antimicrobial use should consistently be made a core component of professional education and continuing competency development (PHAC, 2023).

Nurses and nurse prescribers are well positioned across the healthcare system to make a positive impact on controlling AMR and promoting AMS best practices. To support nurses’ role and involvement in AMS across Canada, the Canadian Nurses Association (CNA) undertook the development of the Antimicrobial Stewardship Competencies: A Pan-Canadian Framework for Nurses (AMS Competency Framework) (Appendix A) that aims to define the knowledge, skills and attitudes required by nurses to effectively promote and participate in AMS within their practice setting and role.

METHODS

The development of the AMS competency framework evolved through a combination of knowledge development based on a review of academic and grey literature, surveys, and focus groups, and validation processes.

Literature review

A literature search was conducted across multiple databases, including Embase, ERIC, Medline, PsychInfo, PubMed, and Scopus. The search strategy used a combination of key terms related to prescribing roles “nurse prescriber”, “non-medical prescriber”, “nurse practitioner”, “nurse” and antimicrobial stewardship concepts (“antimicrobial stewardship”, “AMS”, “nursing stewardship”, “AMS competency”, “AMS education”, “antibiotic*”, “antimicrobial*”, “antibiotic resistance”). Conducted in two phases (November 2019 to November 2021 and December 2021 to August 2022), the search yielded 2,309 articles. Initial screening excluded articles that did not pertain to “nurse” or “nurse prescriber” practice, failed to address the specific competencies (i.e., knowledge, skills, judgment) required for evidence-based antimicrobial stewardship, were not published in English, or were not available in full text. A total of 2,202 articles were removed, resulting in 107 articles selected for full review.

Initially, the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC) conducted a rapid review of 75 articles to describe the AMS role of non-prescribing nurses and nurse prescribers working in long-term care settings, and to identify enablers, barriers, and opportunities for nurse involvement in AMS within the Canadian context. During this review, the need to expand the literature search to all nursing practice settings was identified, and an additional 32 articles were reviewed.

Eight proposed nursing competency domains and specific competency statements within each domain were extrapolated from the literature reviews. As a first step in the knowledge development process, an online cross-Canada survey of nurses was conducted to confirm alignment of these findings with the Canadian nursing practice context.

Survey development

The survey was developed using key documents, frameworks, and a review of relevant academic literature. Survey questions were refined with input from the project’s Steering Committee, Subject Matter Expert Working Group members, and representatives from the PHAC Behavioural Sciences Office. A total of 263 nurses participated; 94% reported practising in non-prescribing roles, and 6% identified as nurse prescribers.

Survey administration

An email invitation, including an introduction and a link to the online survey via the SurveyMonkey platform was broadly circulated in early June 2023 to CNA Academy fellows, 40 specialty networks, and individual CNA members. The link was also shared with the project’s committee members and the PHAC AMS Task Force project team, who distributed it within their nursing networks using convenience sampling and snowball techniques. Due to the broad circulation, the participation rate could not be determined. Survey response rates were monitored weekly; reminder emails were regularly sent, and targeted follow-up encouraged responses from specific geographical areas and practice settings. Preliminary survey results were reviewed three weeks after distribution to inform focus groups held in late June and early July.

Key survey findings and trends were then confirmed and explored further through three virtual focus groups with nurses and nurse prescribers. Each focus group lasted approximately 1.5 hours and was recorded. Transcripts were de-identified and reviewed for emerging themes.

Development of a draft AMS competency framework: The findings from the literature reviews, survey, and focus groups informed an initial draft of the AMS competency framework outlining overarching competency domains and descriptors, as well as the specific AMS knowledge, skills, and attitudes for each area. The draft framework underwent internal review and validation by the Subject Matter Expert Working Group, and a revised version was appraised and approved by the Steering Committee before proceeding to external review.

Framework review and validation process: The external review and validation were conducted using the Delphi method. Preferred reviewer criteria and a list of practice settings and roles were developed. A call for external reviewers was circulated electronically to key nursing groups across diverse geographical locations in Canada to recruit broad representation of nursing roles and practice settings. Volunteers were screened, and those meeting the criteria received an electronic copy of the draft AMS competency framework along with a link to an online feedback form. Reviewers were given four weeks to complete the review and submit anonymous feedback via the form.

A mixed qualitative and quantitative approach was used in the Delphi process. Reviewers responded to open-text questions about the framework’s design and presentation (e.g., Are the competencies applicable across all nursing practice settings and roles? Is anything unclear? Is anything missing?). They also rated each competency statement for inclusion (Yes/No/Unsure) and provided specific suggestions for changes if needed.

Qualitative comments and quantitative feedback were reviewed and incorporated into a revised draft which was validated by the Subject Matter Expert Working Group. The final draft was then presented to the Steering Committee for review and approval before formatting and translation of the AMS competency framework document.

Development of the AMS competency evaluation framework: The evaluation framework was developed concurrently with the AMS competency framework based on a review of relevant literature and exemplar documents. A draft evaluation framework was reviewed by the Subject Matter Expert Working Group, and the final draft was presented to the Steering Committee for approval to be included in the AMS Competency Framework document.

RESULTS

Antimicrobial stewardship survey

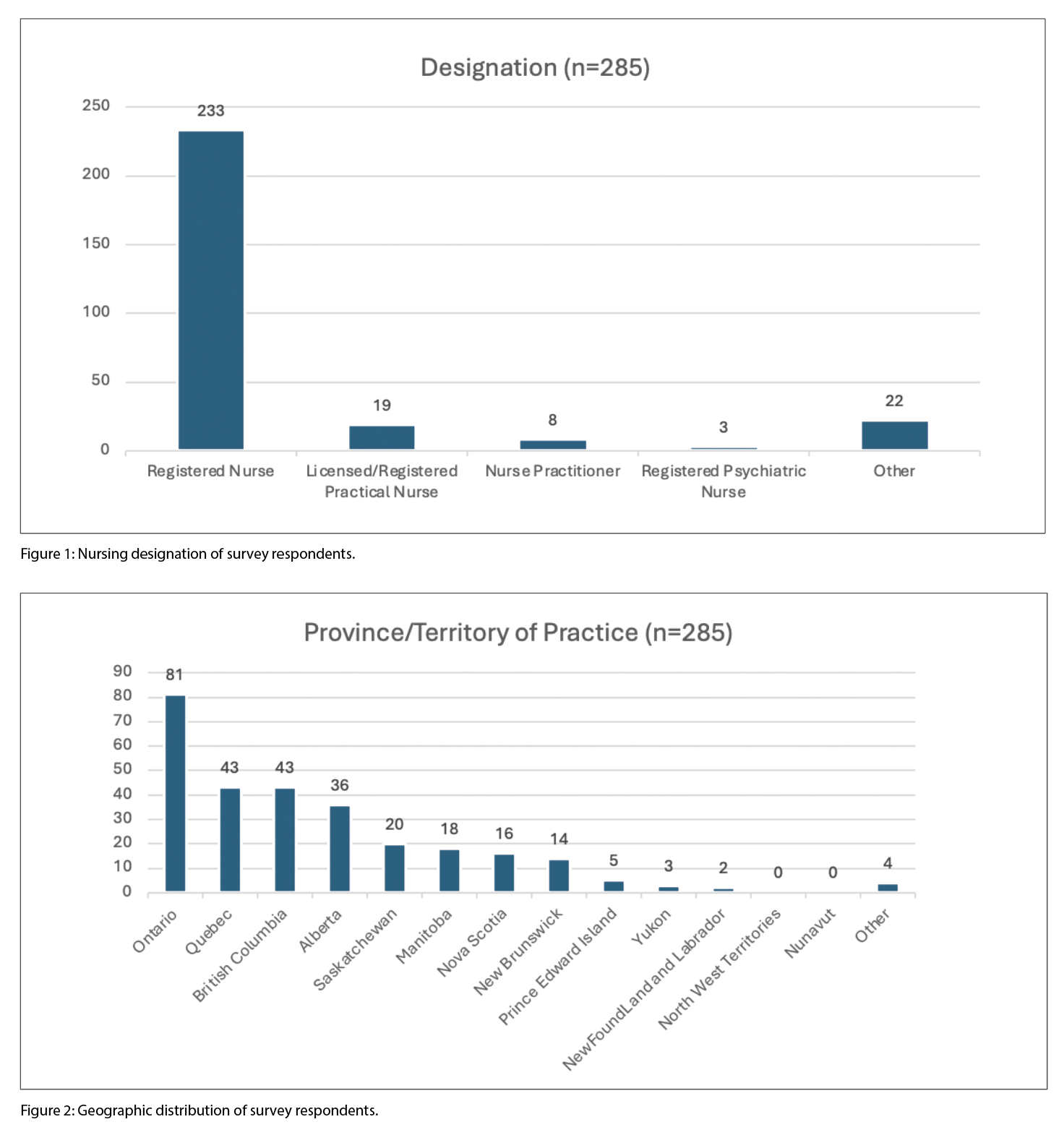

Survey respondents: Responses were received from June 9 to July 7, 2023, with a total of 285 completing the demographic questions. Of these, 22 respondents who selected “other” for nursing designation were excluded to ensure the survey included only regulated nurses. This left 263 respondents who completed the first half of the survey (primer and competency domain questions) and 198 who completed the entire survey (Figures 1 and 2).

Antimicrobial stewardship primer survey questions

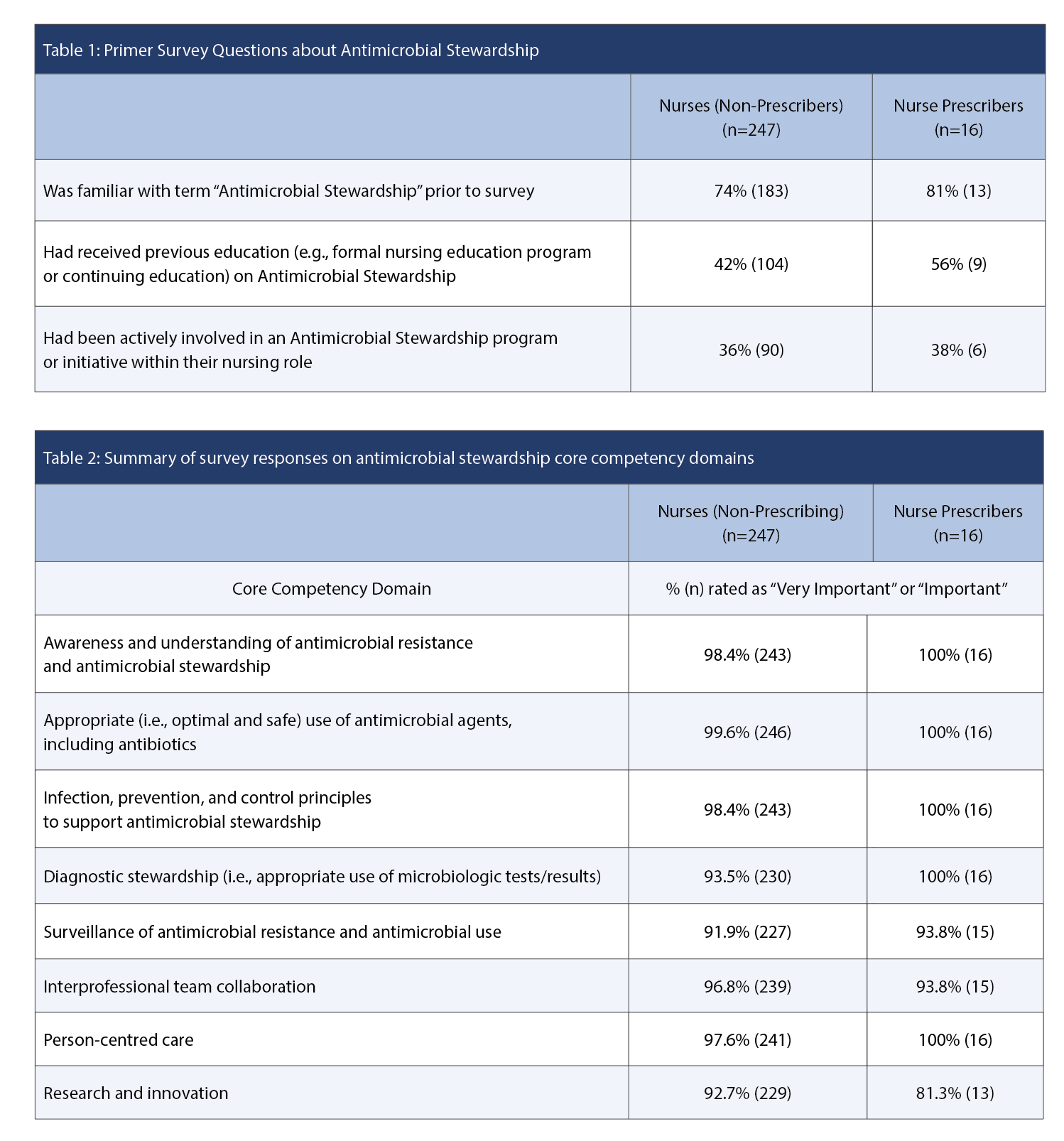

At the start of the survey, nurses (non-prescribers) and nurse prescribers were asked three primer questions (Table 1).

Antimicrobial stewardship core competency domains

The eight competency domains derived from the literature review were presented to participants, and asked to rank each domain as very important, important, somewhat important, or not important for inclusion in the final competency framework. Participant responses for the eight AMS core competency domains are summarized in Table 2.

Knowledge gaps in antimicrobial stewardship

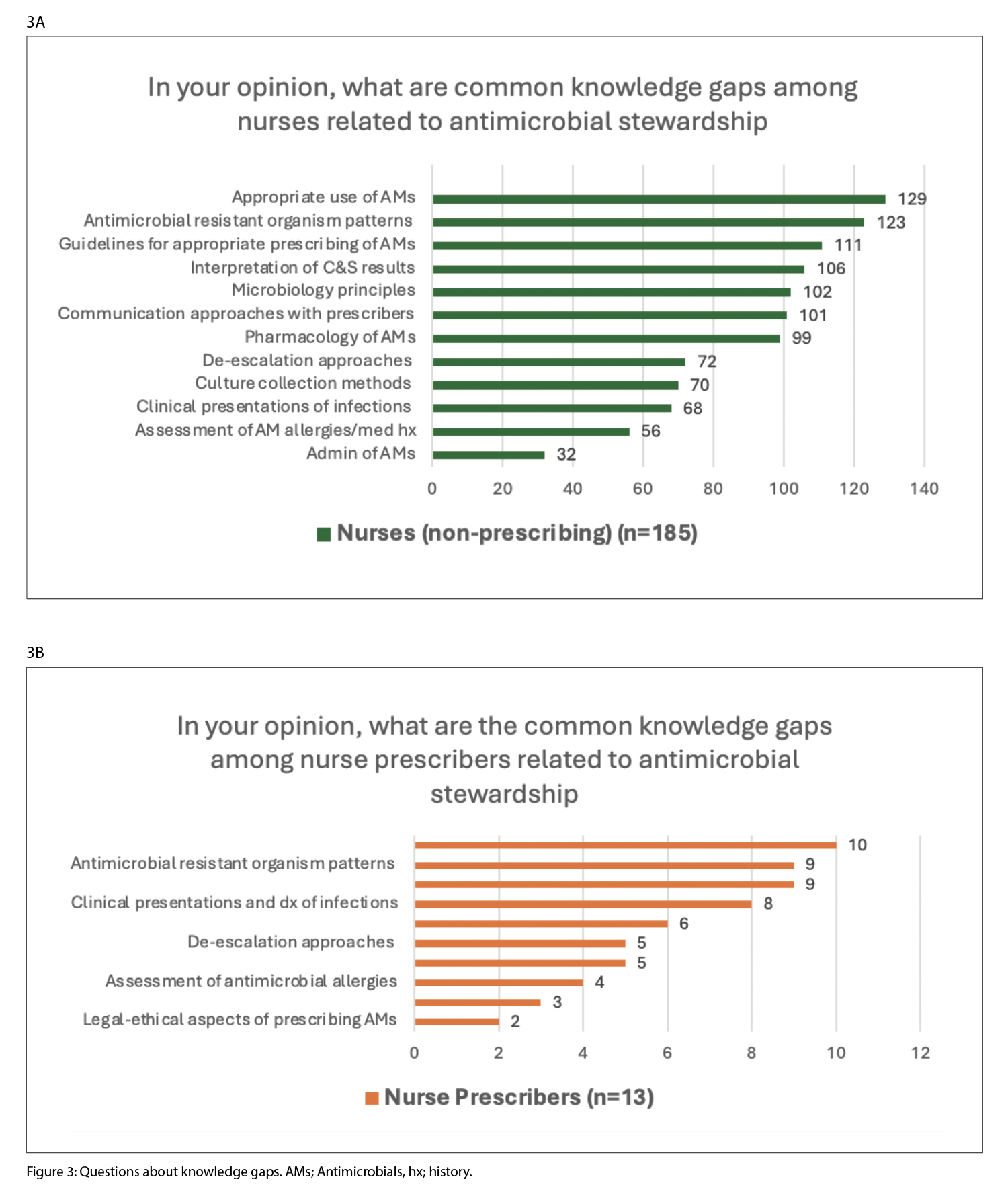

The knowledge gap of nurses in AMS were assessed among 185 non-prescribing nurses and 13 nurse prescribers. The most common knowledge gaps in order of identification are outlined in Figures 3A and 3B for each group.

Barriers to optimizing nurses’ role in antimicrobial stewardship

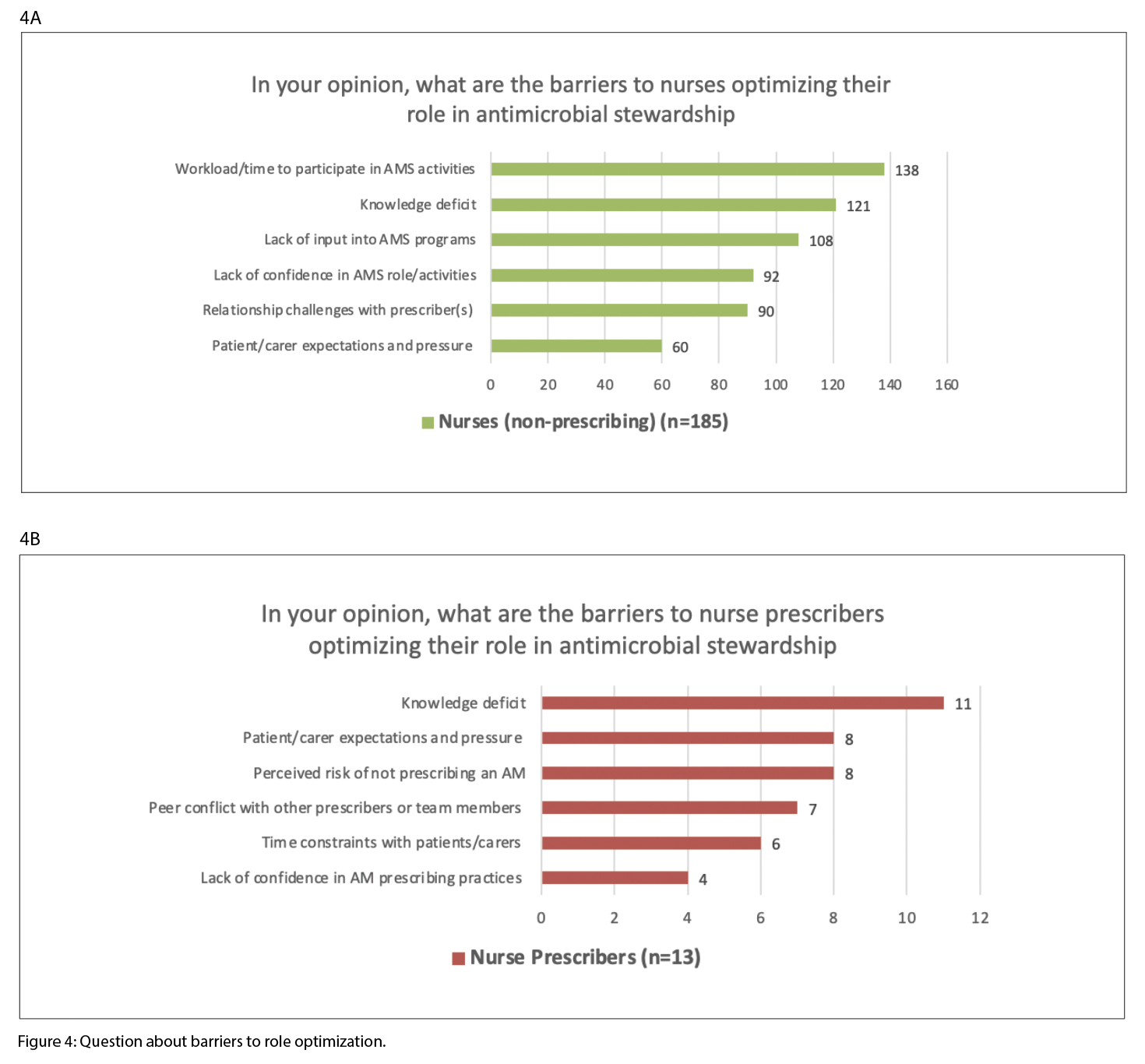

Barriers to optimizing the nurse’s role in AMS were assessed among 185 non-prescribing nurses and 13 nurse prescribers. The most commonly identified barriers for each group are outlined in Figures 4A and 4B.

Opportunities for nurses to optimize their role in antimicrobial stewardship

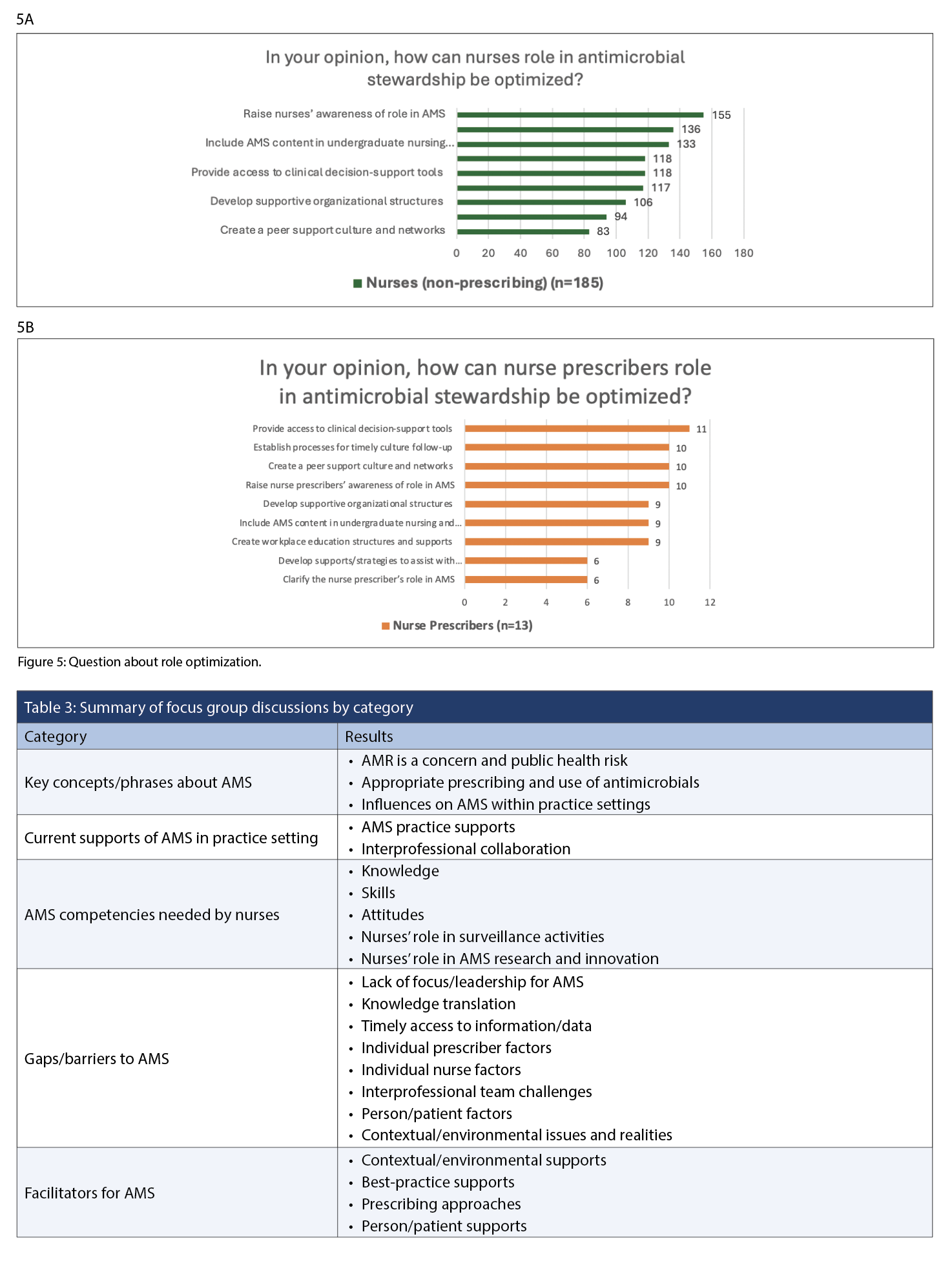

The opportunities for optimizing nurses’ role in AMS were assessed among 185 non-prescribing nurses and 13 nurse prescribers. The most commonly identified opportunities for each group are outlined in Figure 5A and 5B.

Focus groups with non-prescribing and prescribing nurses

Data from the three virtual focus groups – two with nine nurses and one with five nurse prescribers – are outlined in Table 3. Overall, the information showed strong alignment between the two nursing roles.

Integration of feedback into the antimicrobial stewardship competency framework

The initial competency domains and statements outlined in the AMS survey were compared with the combined data from survey and focus group participants. As a result, the eight domains were condensed into seven, with domain 5 – Surveillance competencies – included within the Infection Prevention and Control domain. The language and descriptions of some competency statements were revised for clarity, and their placement within the framework was adjusted. Additional competencies were also added based on participant feedback.

Delphi method

Thirty-three external reviewers participated in the Delphi process to review the revised draft of the AMS competency framework. Reviewers were selected by invitation or institutional nomination considering expertise, sample diversity, interest, and accessibility. Participants included 24 nurses and nine nurse prescribers from diverse geographical areas across Canada, including urban, rural, and remote locations, as well as various clinical practice settings (community: primary care, clinics, public health; long-term and transitional care; acute care: medicine, surgery, critical/emergency care; wound care; occupational/workplace health; correctional) and nursing roles (direct care, infection prevention and control, management, administration/leadership, best practice, education, and academia).

Overall, there was a high level of agreement on the 60 competency statements related to knowledge, skills, and attitudes. All but three statements scored over 90% agreement, with no statement scoring less than 80% agreement for inclusion in the AMS competency framework.

DISCUSSION

An evidence-informed process was undertaken to develop the Antimicrobial Stewardship Competencies: A Pan-Canadian Framework for Nurses (the AMS Competency Framework). The framework defines core competencies that underpin safe and effective AMS practices among nurses and nurse prescribers. These competencies provide a foundation for professional development, education, and quality improvement initiatives adaptable to various healthcare settings and roles.

Importantly, this work aligns with global efforts such as the World Health Organization’s Competency Framework for Health Workers’ Education and Training on Antimicrobial Resistance, which emphasizes multidisciplinary engagement, integration into pre-service education, and interprofessional collaboration (World Health Organization, 2018).

The AMS Competency Framework addresses persistent gaps identified in the literature. For example, nurses frequently report limited understanding of microbiology, resistance mechanisms, and prescribing guidelines (Olans et al., 2015). Similar findings have emerged internationally, where nurses express discomfort in stewardship roles due to inadequate training and unclear responsibilities (Olans et al., 2016; Courtenay et al., 2019). By clearly defining knowledge, skills, and attitudes, the framework promotes nursing leadership and consistency in AMS delivery.

Barriers such as time constraints, lack of access to clinical decision-support tools, and entrenched institutional hierarchies have also been extensively documented (Broom et al., 2016; Redefining the Antibiotic Stewardship Team, 2019). The AMS Competency Framework responds to these challenges by embedding AMS as a shared responsibility, not just for prescribers, but for all nurses, aligning with recommendations by the American Nurses Association and the CDC to formalize nurses’ roles on AMS teams, as well as national strategies such as the Public Health Agency of Canada’s antimicrobial resistance surveillance initiatives (PHAC, 2018). It supports the standardization of AMS education and accountability in both prescribing and non-prescribing nursing roles. Unlike physician-centric models, this framework empowers nurses in long-term care, acute care, and community health settings – sectors identified as critical but often under-resourced in stewardship efforts (Morrill et al., 2016; Scales et al., 2017).

The integrated AMS Competency Evaluation Framework enables structured self-assessment and performance monitoring. While contextual factors such as workload and scope of practice may affect uptake, prior evidence suggests that clearly defined competencies enhance prescribing accuracy and foster an interprofessional AMS culture (Dyar et al., 2017; Lim et al., 2018).

LIMITATIONS

This study acknowledges several limitations. The literature review was conducted as a rapid review, as a result, this may not have captured the full breadth of evidence that a systematic review would provide. Survey participation from Eastern Canada and the Northern Territories was lower than desired. Although targeted efforts engaged nurses from these regions in focus groups and the Delphi process, the under-representation of these regions remain. Also, Northern Territory experts, despite initial agreement were unable to participate due to unforeseen circumstances (forest fires). Additionally, while the survey included authorized nurse prescribers, the focus groups primarily involved Nurse Practitioners; no Registered Nurses with prescribing authority participated. Despite these limitations, a multi-faceted approach across study components was employed to mitigate potential biases and enhance the comprehensiveness of the findings.

CONCLUSION

Although grounded in the Canadian context, this framework has international applicability. Unlike models that focus solely on prescribing behaviours (Ness et al., 2016; Nuttall, 2018), this framework adopts a holistic approach to support AMS practice across all nursing categories and care environments.

In summary, the AMS Competency Framework offers a timely, evidence-informed tool to support the structured integration of AMS into nursing practice. It reinforces Canada’s commitment to reducing antimicrobial resistance and advances global efforts to elevate nursing leadership in antimicrobial stewardship.

As antimicrobial resistance continues to threaten global health, empowering nurses through structured, evidence-informed AMS competencies is both timely and essential. The Antimicrobial Stewardship Competencies: A Pan-Canadian Framework for Nurses provides a foundational tool to enhance nursing capacity and leadership across all roles and settings. By addressing longstanding knowledge gaps, practice barriers, and the need for role clarity, the framework promotes a more consistent nursing contribution to AMS efforts.

Its alignment with global standards such as the WHO AMS Competency Framework, and national priorities outlined by the Public Health Agency of Canada ensures its relevance both domestically and internationally. Furthermore, by integrating an evaluation component, the framework supports reflective practice, accountability, and continuous quality improvement. Moving forward, its implementation offers a critical opportunity to strengthen interprofessional collaboration, optimize antimicrobial use, and ultimately safeguard the efficacy of antibiotics for generations to come.

REFERENCES

Broom, A., Broom, J., Kirby, E., & Scambler, G. (2016). Nurses as antibiotic brokers: Institutionalized praxis in the hospital. Qualitative Health Research, 27(13), 1924–1935. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732316672641

Canadian Nurses Association. (2023). Antimicrobial stewardship competencies: A pan-Canadian framework for nurses. Ottawa, ON: Canadian Nurses Association. https://www.cna-aiic.ca/en/policy-advocacy/advocacy-priorities/antimicrobial-resistance

Courtenay, M., Castro-Sánchez, E., Gallagher, R., McEwen, J., Bulabula, A., Carre, Y., … Monks, S. (2019). Development of consensus-based international antimicrobial stewardship competencies for undergraduate nurse education. Journal of Hospital Infection, 103(3), 244–250. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhin.2019.07.010

Dyar, O. J., Pagani, L., & Pulcini, C. (2017). Strategies and challenges of antimicrobial stewardship in long-term care facilities. Clinical Microbiology and Infection, 21(1), 10–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmi.2014.09.005

Lim, A. G., North, N., & Shaw, J. (2018). Beginners in prescribing practice: Experiences and perceptions of nurses and doctors. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 27(5–6), 1103–1112. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.14136

Morrill, H. J., Caffrey, A. R., Jump, R. L., Dosa, D., & LaPlante, K. L. (2016). Antimicrobial stewardship in long-term care facilities: A call to action. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 17(2), 183.e1–183.e16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2015.11.013

Ness, V., Price, L., Currie, K., & Reilly, J. (2016). Influences on independent nurse prescribers’ antimicrobial prescribing behavior: A systematic review. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 25(9–10), 1206–1217. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.13249

Nuttall, D. (2018). Nurse prescribing in primary care: A metasynthesis of the literature. Primary Health Care Research & Development, 19(1), 7–22. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1463423617000500

Olans, R. D., Nicholas, P. K., Hanley, D., & DeMaria, A. (2015). Defining a role for nursing education in staff nurse participation in antimicrobial stewardship. Journal of Continuing Education in Nursing, 46(7), 318–321. https://doi.org/10.3928/00220124-20150619-04

Olans, R. N., Olans, R. D., & DeMaria, A. Jr. (2016). The critical role of the staff nurse in antimicrobial stewardship—Unrecognized, but already there. Clinical Infectious Diseases, 62(1), 84–89. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/civ697

Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC). (2023). Pan-Canadian action plan on antimicrobial resistance. https://www.canada.ca/content/dam/phac-aspc/documents/services/publications/drugs-health-products/pan-canadian-action-plan-antimicrobial-resistance/pan-canadian-action-plan-antimicrobial-resistance.pdf

Redefining the antibiotic stewardship team. (2019). Recommendations from the American Nurses Association/Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Workgroup. JAC-Antimicrobial Resistance, 1(2). https://doi.org/10.1093/jacamr/dlz037

Scales, K., Zimmerman, S., Reed, D., Beeber, A. S., Kistler, C. E., & Preisser, J. S. (2017). Nurse and medical provider perspectives on antibiotic stewardship in nursing homes. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 65(1), 165–171. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.14504

World Health Organization (WHO). (2018). WHO competency framework for health workers’ education and training on antimicrobial resistance. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/who-competency-framework-for-healthworkers-education-and-training-on-antimicrobial-resistance

Acknowledgements: The development of Antimicrobial Stewardship Competencies: A Pan-Canadian Framework for Nurses was coordinated by the Canadian Nurses Association (CNA) in partnership with the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC), which provided funding and support. CNA gratefully acknowledges the expertise, dedication, and contributions of the members of the Antimicrobial Stewardship (AMS) Competencies for Nurses Steering Committee and the subject matter expert working group. CNA also thanks the nurses from various Canadian practice settings who contributed insights by responding to the online AMS survey, participating in AMS focus groups, or serving as external reviewers of the draft framework.

Conflicts of interest: Authors report no conflicts of interest.